by

_____

Driven by a keen moral compass and sharp legal mind, Constance Baker Motley spent four decades dismantling Southern race laws, fighting discrimination, and advancing human rights.

But it was her public voice that first opened doors for her own advancement and opportunity.

She was the daughter of immigrants from the West Indies, the ninth of twelve children, and grew up in a working class neighborhood in New Haven. Higher education was certainly not in the cards.

“There was no money for me to go to college,” she recalled in a speech in 1993 when she was inducted into the Women’s Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, New York. “I went to work at the National Youth Administration, and one day I gave a speech at a black community house.”

In the audience was philanthropist Clarence Blakeslee — he was so taken by her talk he asked her afterwards where she’d be going to college. When she told him her parents couldn’t afford it, he agreed to pay for her education. She graduated from NYU and Columbia Law School.

In a remarkable career from 1946 until her semi-retirement in 1986, Motley became a key legal strategist in the Civil Rights movement, helping to end segregation in housing, transportation, recreation, and public accommodations across the South.

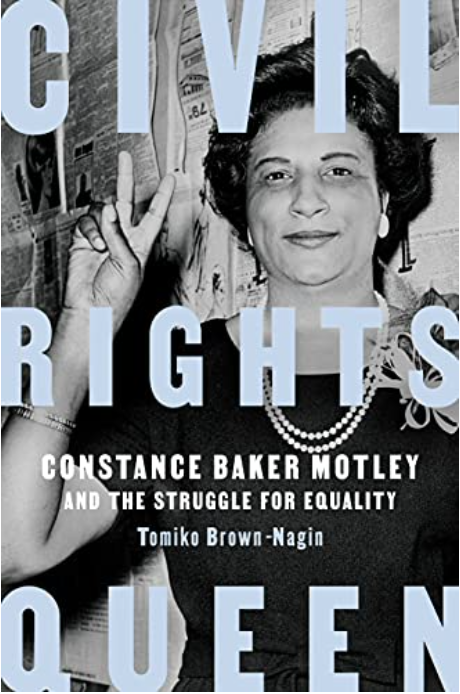

Now comes a new biography of Motley, Civil Rights Queen: Constance Baker Motley and the Struggle for Equality, by Tomiko Brown-Nagin, dean of the Harvard Radcliffe Institute.

While still a law student at Columbia, Motley was hired by Thurgood Marshall to become his legal clerk at the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

At first she worked on housing cases, fighting to break the restrictive covenants that kept Blacks out of white neighborhoods.

She began appearing before state and federal courts across the US in civil rights matters.

Motley was one of the lawyers who helped write the briefs filed in the historic Brown v. Board of Education desegregation case.

She directed the legal campaign that led to the admission of James Meredith to the then segregated University of Mississippi in 1962 — a key victory for the Civil Rights movement.

She was the first Black American woman to argue a case before the US Supreme Court. By the time she left the NAACP in 1965, she had argued ten crucial cases before the Supreme Court, and won nine of them.

She then entered New York politics, becoming the first Black woman in the State Senate, where she worked to extend civil rights legislation and for low and middle-income housing. Then she became the first woman to be Manhattan Borough president.

In 1966, President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed Motley to the federal bench in the Southern District of New York — yet another historic “first” — she was the first Black woman to hold that position.

In April 1996, she spoke at a luncheon in honor of Thurgood Marshall at the New York Bar Association. It had been a century since the notorious Plessy v. Ferguson case that upheld the constitutionality of racial segregation as “separate but equal.”

In her resonant, low-timbered voice, Motley delivered a moving history lesson, tracing the nation’s long struggle for racial equality, from the struggle to end slavery to the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the many accomplishments beyond.

“The struggle for racial justice is like a prairie fire,” she said. “You may succeed in stamping out the struggle for equality in one corner and, lo and behold, it appears soon thereafter somewhere else.”

And yet, she noted, “notwithstanding all of the opposition to equal status for blacks in the American community, blacks have never occupied a more equal status in society than we do today.”

In no small measure, we have Constance Baker Motley vision, advocacy, and voice to thank for that.

© Copyright 2022

________________________________

Want to talk? Reach me at dana@danarubin.com